The world of book publishing is constantly changing. And yet, somehow, book editors remain the trusty lifeboats keeping manuscripts afloat. As we charge into 2025, book editing services are adapting to new tech and evolving reader expectations faster than I can finish my to-be-read pile (which, let’s be honest, isn’t happening anytime soon).

So, what’s the deal with book editing these days? Let’s explore why editors are still your best friends, and how to pick the right one for your future bestseller.

What Book Editors Do

Book editors play a vital role in transforming raw manuscripts into polished, publishable works. Sure, they fix your grammar (thank goodness), but that’s just scratching the surface.

Editors are like story surgeons—they slice and dice your manuscript until it’s lean, polished, and ready to knock the socks off readers. Whether it’s reworking plot holes the size of the Grand Canyon or making sure your characters aren’t walking clichés, editors are the unsung heroes of the publishing world.

Here’s a breakdown of what these word wizards do to take your book from “eh” to “wow.”

Proofreading vs. Editing

While often used interchangeably, proofreading and editing are distinct processes. Let’s take a moment to untangle this a bit:

Proofreading: This is the final stage of the editing process. Proofreaders focus on correcting surface errors in spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting. They ensure consistency in style and catch any lingering typos or mistakes that might have been missed in earlier editing rounds.

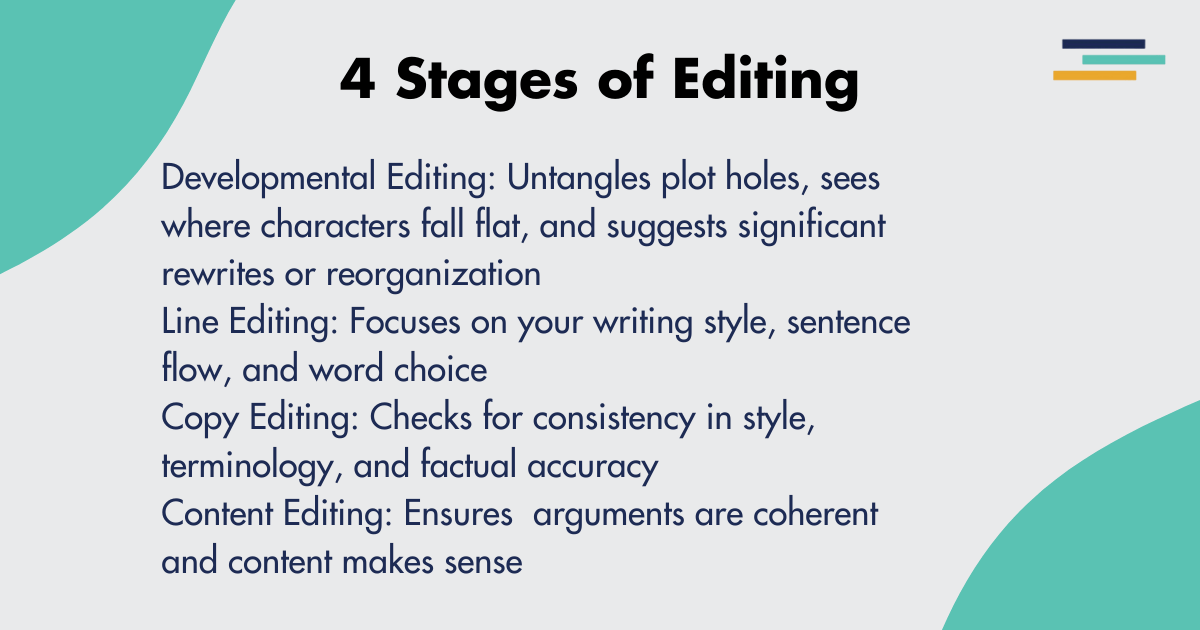

Editing: This is a more comprehensive process that involves improving the overall quality of the writing. Editing can be further divided into four types:

- Developmental Editing: This is the most intensive form of editing. Developmental editors help you untangle plot holes, point out where characters fall flat, and suggest major rewrites or structural changes. They may suggest significant rewrites or reorganization of content.

- Line Editing: This focuses on your writing style, sentence flow, and word choice. They make your text sing by tightening up awkward sentences, cutting unnecessary words, and making sure every paragraph flows smoothly.

- Copy Editing: The rule-followers of the editing world. This involves checking for consistency in style, terminology, and factual accuracy. Copy editors also address issues with grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

- Content Editing: This one’s especially important in non-fiction. Content editors ensure that your arguments are coherent, your research is solid, and your content makes sense for your intended audience. This type of editing focuses on the accuracy and completeness of the content, especially in non-fiction works. Content editors may suggest additional research or fact-checking.

Most editors wear multiple hats and offer a blend of these services. It’s all about tailoring the process to your needs.

Benefits of Professional Book Editing Services

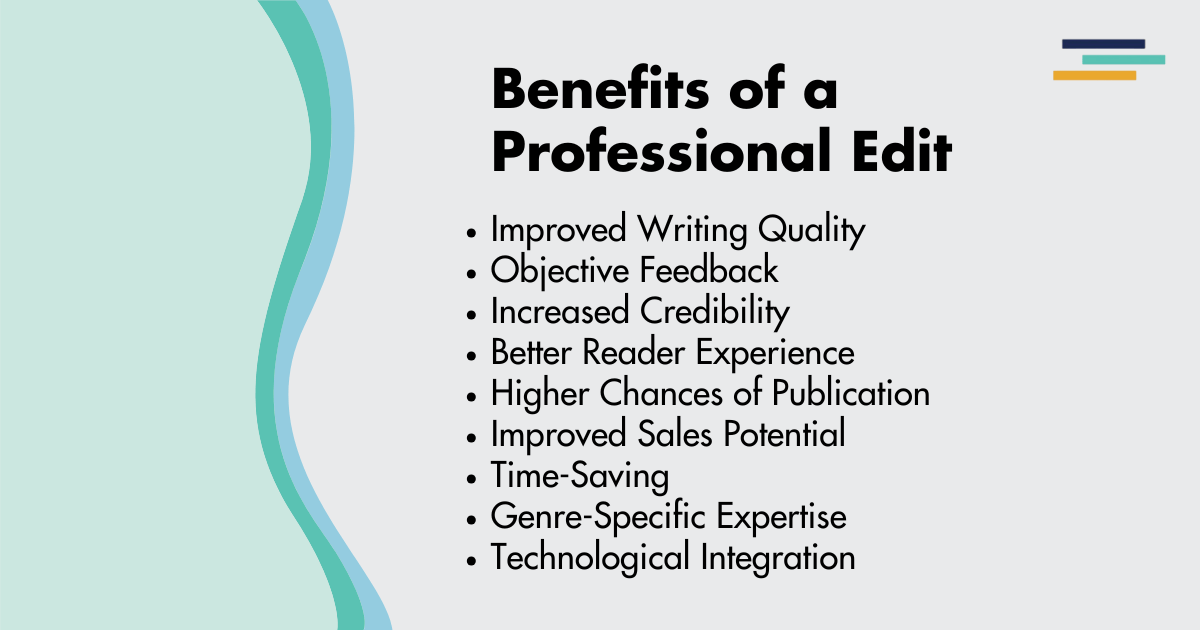

Investing in professional book editing services can significantly impact the quality and success of your book. Here are some key benefits:

- Improved Writing Quality: Professional editors help refine your writing style, making your prose more engaging and impactful.

- Enhanced Clarity: Editors ensure your ideas are conveyed clearly and coherently, improving reader comprehension.

- Objective Feedback: An experienced editor provides valuable, unbiased feedback on your work, helping you identify strengths and areas for improvement.

- Increased Credibility: A well-edited book demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail, enhancing your credibility as an author.

- Better Reader Experience: By addressing issues with pacing, structure, and flow, editors help create a more enjoyable reading experience.

- Higher Chances of Publication: For authors seeking traditional publishing, a polished manuscript is more likely to catch the eye of agents and publishers.

- Improved Sales Potential: For self-publishing authors, a professionally edited book is more likely to receive positive reviews and word-of-mouth recommendations, potentially leading to increased sales.

- Time-Saving: Professional editors can spot and fix issues much faster than most authors, saving you valuable time in the revision process.

- Genre-Specific Expertise: Many editors specialize in specific genres, offering insights tailored to your book’s target audience and market expectations.

- Technological Integration: In 2025, many editing services incorporate AI-assisted tools to enhance their work, providing even more comprehensive feedback and suggestions.

Fictionary’s Book Editors

Fictionary is a cutting-edge platform designed to help writers and editors alike, focusing on the crucial elements of storytelling such as plot, character development, and structure.

One of the biggest benefits for writers working with Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Editors is that these editors have undergone specialized training in story structure and scene analysis. They focus not only on the technical aspects but also on the overall flow and cohesion of the narrative, ensuring that everything from character goals to conflict and tension is sharpened.

Certified StoryCoach Editors use the 38 Fictionary Story Elements to evaluate key components like entry/exit hooks, POV anchors, pacing, and emotional arcs in every scene. This systematic approach allows editors to identify weaknesses that might otherwise go unnoticed, transforming a draft into a cohesive, compelling story.

In addition to delivering precise, actionable feedback, StoryCoach also generates visual reports, like a Story Arc, to give authors a clear picture of how their manuscript measures up to professional standards. This combination of technology and editorial expertise helps ensure that a writer’s voice shines through while making the necessary adjustments to improve their story.

With the rise of online editing tools like Fictionary, writers today have amazing access to high-quality editorial services. By working with a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Editor, you can be confident that your story will receive a professional, thorough edit that focuses on improving the core elements of your story.

Let’s explore some of Fictionary’s top editors and their areas of expertise:

Angie Andriot

I help fiction authors make their books soar. My specialty is speculative fiction. I love all things fantasy, sci-fi, and horror. When you work with me, you get a wholehearted advocate for your writing. As your editor, I will nurture your unique voice, guide you to uncover the essence of your story, and help you craft a fantastic novel.

I offer developmental editing, book coaching, and soul care for writers.

Kathrin Auzinger

As a fellow writer, I resonate with the desire to weave captivating tales that keep readers engaged from start to finish. But what’s the secret ingredient that turns an ordinary tale into a captivating experience? Edit, refine, and revise.

Brandi Badgett

When you have someone kind and knowledgeable to guide you, you can discover hidden depths to your writing that you never knew were there! I love discovering new and exciting ways to make Fictionary’s 38 elements shine in a story.

I will apply my daily expanding skills of story craft to your horror, romance, historical, fantasy, or sci-fi.

Ali Bumbarger

I am passionate about helping writers build their stories to their fullest potential. As a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach editor, I am here to encourage and support you while providing an objective, structural edit on your manuscript. I will honor your vision and artistry, while offering actionable advice to help you strengthen your unique story and create a novel readers love.

Adrienne Deeb

As a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Editor, I will delve deep into your story. Together, we will brainstorm, tweak, and perfect your manuscript, using Fictionary’s thirty-eight elements for structure. This is your story, and I’d be honored to help you make it shine.

James Gallagher

As a Fictionary-Certified StoryCoach Editor, I am eager to help you tell your story. I have a special fondness for horror, romance, and genre fiction, and I’m both a developmental editor and a copy editor.

Randal Gilmore

As a Fictionary Certified Editor, I would be honored to work with you. My passion is developmental editing. I will use StoryCoach to sift through your story scene by scene, and story element by story element.

My goal is to empower and motivate you to do your finest work. In the end, you will receive an edit that is comprehensive, objective, and actionable. And because it will be delivered to you in kindness, you’ll be motivated to see your project through. Let’s take this journey together!

Rachel Hills

Using Fictionary, I provide an objective edit tethered to your artistry. In addition, I offer two decades’ experience in editing (copy, line, and developmental) paired with training in book coaching and ghostwriting.

Pamela Hines

Pamela is a certified Story Grid editor, developmental editor, copyeditor, and book coach. She will combine her Story Grid knowledge with technology and use Fictionary StoryCoach software to provide you with an exceptional story edit.

Linda O’Donnell

As a Certified Fictionary StoryCoach Editor, I want to help others overcome their stumbling blocks and conquer their fears by delivering a comprehensive edit that focuses on making their story one that is structurally sound and reflects their vision and voice. Kindness is at the core of all I do, so don’t be afraid. I promise it won’t hurt!

Romance, mysteries, thrillers, general fiction, and mashups are all up my alley!

Emily Park

As a writer you have the power to transport readers, move them to tears and even alter their view of the world. I have a particular interest in the genres of Fantasy, mystery, and horror but every now and then I indulge in historical romance.

My job as a Fictionary StoryCoach editor is to support you in creating a story that readers will want to devour. Using Fictionary, I will give positive, in depth advice that is actionable in transforming your story. My goal is that you feel confident in your voice as an author and in the message you are writing to convey. The editing process can be harrowing but I am here to support you to create the compelling story you envision.

Jo Taylor

What is the difference between a story told at a party, and a story told by a comedian on stage? Editing. It’s the same writer, the same story, but by the time it gets to the stage, it’s been structured and crafted for maximum effect. Another pair of eyes, another reader, an editor will help you to create the story you want to tell.

I love literary fiction and paranormal. I also specialize in stories which are heavy with medical scenarios, as I was an ER Nurse for twenty-five years.

Lisa Taylor

Stories are powerful. Through my experience as an educator and librarian, I’ve explored how stories work and supported writers in finding their voices and honing their craft.

As a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Editor, I offer a thorough, objective structural story edit that honours your voice, recognises and celebrates your skill, and offers clear, actionable ideas on ways to make your story shine even more.

Robinette Waterson

Every writer is equipped with 26 letters, a handful of punctuation marks, and a mission to find the story within their heart, yearning to be free. What do you want to say today?

Robinette Waterson enjoys helping writers answer that question. As a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Editor, she can offer writers a sound grounding in story structure, including assessing strong characterization, crafting a compelling plot, and building an immersive setting for the reader.

Polly Watt

A former refugee lawyer in the UK, Polly Watt honed her skills working on cases where careful editing often really was a matter of life and death.

As a Fictionary StoryCoach Editor, she will apply the same care and attention to detail to your structural story edit. She’s passionate about stories and loves working on all different types of literary genres.

Emily White

I’m a Fictionary Certified Editor who reads, writes, edits, and coaches across multiple genres. Simply put, I love a good story.

My genuine passion is helping authors shape captivating narratives through developmental editing. I evaluate each scene against 38 story elements to ensure a compelling story and strong connections throughout the manuscript. You have a unique voice; my job is to motivate and coach you to make your work stand out. If you’re ready for an in-depth, objective critique with actionable advice, I’m here to help!

Heather Wood

By combining my experience of teaching writing at the secondary level with a Fictionary StoryCoach Edit, I will help you strengthen your story while honoring the care and effort you have dedicated to your art.

Tips For Selecting the Best Book Editor For You

Choosing the right editor is crucial for the success of your book. Here are some tips to help you make the best decision:

- Define Your Editing Needs: Determine what type of editing your manuscript requires. Are you looking for developmental editing, line editing, or just a final proofread? Understanding your needs will help you find an editor with the right expertise.

- Consider Genre Expertise: Look for an editor who has experience in your specific genre. They’ll be familiar with conventions and reader expectations, providing more targeted feedback.

- Review Their Portfolio: Ask potential editors for samples of their work or a list of books they’ve edited. This will give you an idea of their style and the quality of their work.

- Check Qualifications and Experience: Look for editors with relevant education, certifications, or membership in professional organizations like the Editorial Freelancers Association.

- Request a Sample Edit: Many editors offer a sample edit of a few pages of your manuscript. This can help you gauge their editing style and determine if it aligns with your vision.

- Discuss Their Process: Understanding how an editor works can help you determine if their process suits your needs and working style.

- Consider Communication Style: You’ll be working closely with your editor, so it’s important to find someone whose communication style meshes well with yours.

- Read Client Testimonials: Look for reviews or testimonials from previous clients to get an idea of the editor’s strengths and how they work with authors.

- Clarify Terms and Conditions: Ensure you understand the editor’s rates, turnaround time, number of rounds of editing included, and any other terms before committing.

- Trust Your Instincts: After considering all the above factors, trust your gut feeling. Choose an editor you feel comfortable working with and who you believe will help bring out the best in your writing.

As we navigate the world of book editing in 2025, finding the right editor for your work is more crucial than ever. The right editor does more than polish your manuscript—they elevate it from good to great, giving you a competitive edge in today’s crowded publishing landscape.

Hiring an editor is an investment in your writing career. Take the time to find an editor who understands your vision. This partnership is key to turning your creative goals into reality.

With platforms like Fictionary connecting authors with skilled editors, there’s never been a better time to seek editing guidance. Embrace the collaborative magic of the author-editor relationship, and watch your manuscript transform into a polished, compelling work.