Introduction: The Story Element

Using one story element will not create a great story. A story is a collection of scenes woven together to illuminate an overarching issue. The issue may be world-shattering as war or redemption. Stories operate on multiple levels. The overall story carries meaning as characters progress toward an object of desire. On another level, every scene’s goal and conflict represent the characters’ actions, struggles, decisions, and lessons.

Every scene must touch on and carry these points through to the end. Making certain story elements blend into a cohesive whole is critical to the revision process. Developmental editors often create story maps or spreadsheets to track the most important macro and micro-story elements.

Your choice of elements to track will depend on the story aspect you’re investigating. You might want to zoom out to the global story or track setups and payoffs, clues and red herrings, revelations, turning points, or character arcs.

This article will discuss ten story elements you need to know for a high-level view of the global story. You can swap them with whichever other element you need, and that’s the beauty of a story map. It’s flexible.

What is a Story Element?

Story elements are the building blocks of your story. They are necessary components. Think of them as the obligatory ingredients of a recipe. Leave one out; you’ve got a cracker instead of a fluffy loaf of bread. Or worse, it may look like bread but taste like cardboard. The story elements are not used alone. They must be used in conjunction with the story arc.

Story Elements and the Revision Process

A revision requires an objective view of the story’s parts. Begin a revision by revisiting your blurb and verifying the story’s narrative perspective, protagonist, story goal, antagonist, character arc, setting, and theme.

Ten elements to track your global story:

- Scene name

- Scene purpose

- POV character

- POV goal

- Characters

- Setting location

- Setting date/time

- Scene goal

- Entry hook

- Exit hook

Scene name, Scene purpose, and POV goal help you track the story trajectory or story spine. POV character and Character arc track the POV character’s external goal. Listing Characters (in the scene and off stage) helps you consider character function, time character introduction, balance perspectives, and prevent lost story threads. Location and Date/Time anchor the settings creating cohesion between people and the environment. Entry hooks establish the scene and engage the reader to read on. Exit hooks turn the scene and propel the reader forward.

Story Element: Scene name

Begin revising your story by naming each scene. This story element is more than it seems at first glance. A scene’s name summarizes its essence with only a few words, ideally two to three. This name should encompass the scene’s overarching action, outcome, or theme. Once crafted, the scene name identifies the scene and is the first item on a story map, scene list, or outline.

Using an economy of words means the scene has focus. A long, meandering scene set in three locations with four major revels is challenging to describe in a few words. Struggling to find a succinct scene name is a sign the scene needs restructuring.

Scene purpose

Every scene in the book must be there for a reason. This story element is about the scene’s function, which can be defining or developmental. Defining purposes include the big story plot points such as inciting incident or midpoint, or genre obligatory moments such as lovers meet, the final showdown, or the hero at the mercy of the villain. Developmental scene purposes include introducing characters, clues and red herrings, establishing the mood or a magic system, or raising stakes or intensifying conflict. If you don’t know the scene’s purpose, leave a mark indicating this. Later, when you look at your map, these will stand out. Scenes with no purpose need revision or don’t have a place in your book.

POV character

The reader experiences the story through the point of view character’s eyes. You want your audience to attach to this character. Grounding in this perspective requires you to identify this character and stick with their viewpoint. Slipping into other characters’ thoughts can jar and confuse the reader.

Tracking your story with multiple POV characters allows you to see how they balance out. If your story has a single POV character, listing them repeated may seem unnecessarily redundant, but it’s not. A story map will show how the story elements align and present an opportunity to verify that this was the best POV choice for the scene.

POV goal

The Point of View (POV) goal is the POV character’s scene goal. Goals move stories forward. Readers run through scenes driven by their empathy with the character, interest in that character’s goals, and concern over them achieving the goal. The goal should align with the scene’s purpose and make sense for this POV character. If the goal is unclear, mark it so you can track it, then look at your completed story map and ask what goal might best fit this moment.

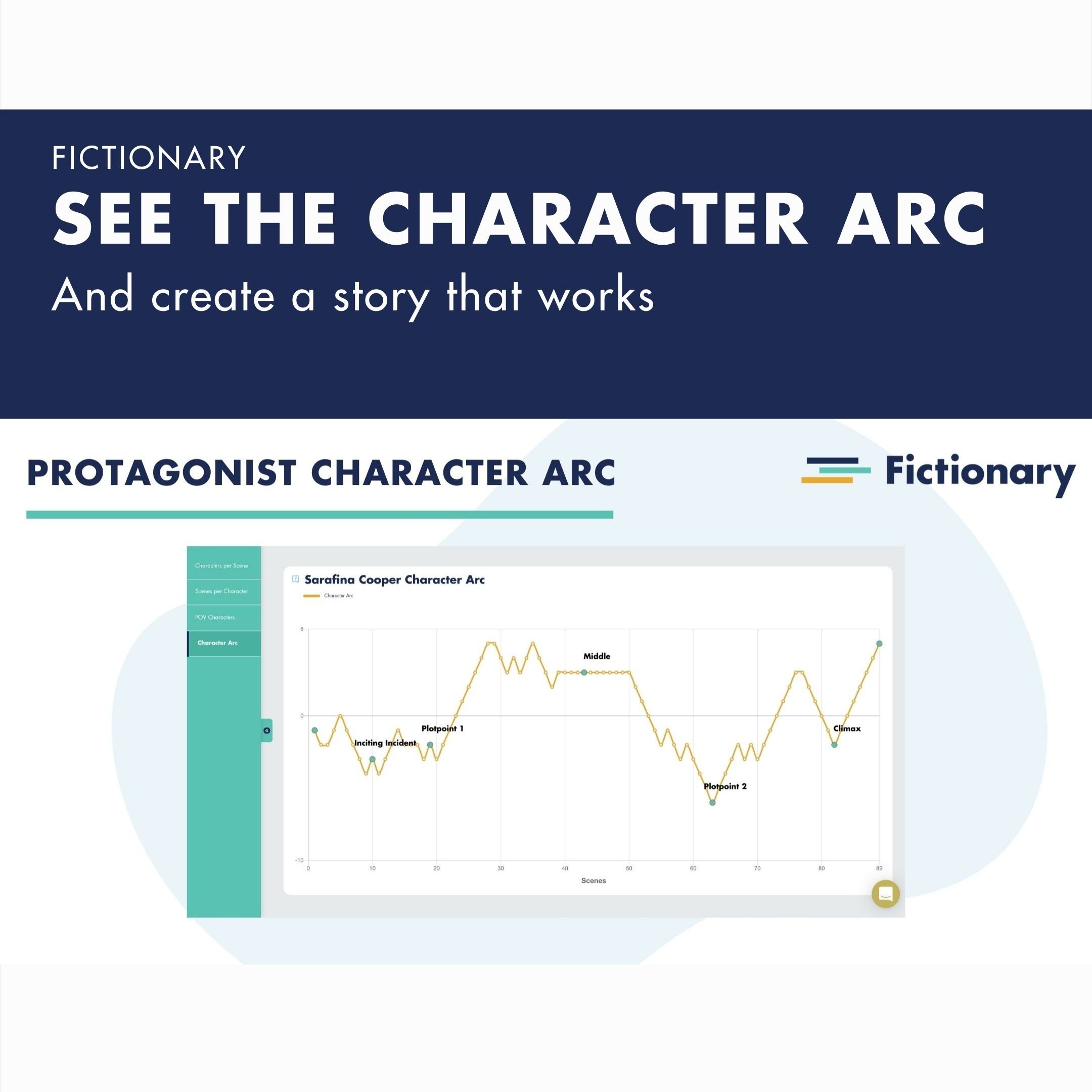

Story Element: Character arc

The character arc is the protagonist’s movement toward attaining their external story goal. The POV goal is scene focused, while the character arc relates to the overall story. Every scene must touch on the external story goal and show the protagonist closer or further from that goal. This deepens understanding of the character and increases reader empathy and concern. Take care to mix wins and losses and ensure they are relevant to the scene’s purpose. On your story map, you’ll be able to see the arc progression toward the story climax and make needed adjustments.

Characters (in the scene and off stage)

Readers engage with characters and attach importance to characters with names and descriptions, not just the protagonist. List the characters present in the scene and those characters introduced or mentioned. Consider each character’s role in the scene and continuity in the story. Are they needed? Has anyone dropped off the map?

All your characters exist in the story world, not just a scene. What are the off-stage characters doing? Has someone important dropped out of scenes? If mentioned but never in a scene, what’s that character’s purpose? Some may establish the inciting incident, protagonist wound, or a critical revelation.

Date/Time

The reader must know as soon as possible in a scene when it occurs. Whether the date and time are in the chapter title, story description, or dialogue, it’s essential to anchor the reader quickly. Some opinions include time passed since the last scene (“the next day”), a time of day (“evening”), or a specific date or time (“23:59”.)

Entry hook

Grab your reader’s interest by starting scenes with an excellent hook to draw them into the scene and prompt them to read on. Hooks needn’t be shocking or contrived. They may start amid the action, deliver a compelling line of dialogue, foreshadow a provocative outcome, or raise a question. Your goal using this story element is to interest and engage.

Exit hook

Exit hooks propel the story forward. Your character has either achieved the scene goal or not and won or lost along their character arc. How do they react to this? Did they win only to be hit with something new? End things so that the reader up wants to know what happens next. This story element keeps the reader turnin the page.

Want to learn more? Check out the 38 Fictionary Story Elements.

Post Written by Pamela Hines

Pamela is a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach editor and a certified Story Grid editor. She will combine her Story Grid knowledge with technology and use Fictionary StoryCoach software to provide you with an exceptional story edit.

Pamela is a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach editor and a certified Story Grid editor. She will combine her Story Grid knowledge with technology and use Fictionary StoryCoach software to provide you with an exceptional story edit.