In this article, we’ll examine:

- The definition and meaning of stock characters,

- Why they can be useful for your story, and

- How to write them well

Stock Character Definition

Search online, and you’ll find slight variations on the definition of a stock character. To understand what a stock character is, it can help first to understand what it’s not.

There are two ‘types’ easily confused with stock characters: archetypes and stereotypes.

Archetypes

An archetype is “The original pattern or model of which all things of the same type are representations or copies.” Archetypes provide guidance as to a character’s role in a story: the mentor, hero, trickster, villain, etc.

Character archetypes are broad, allowing for substantial flexibility in character representation.

Stereotypes

A stereotype is, “Something conforming to a fixed or general pattern. Especially: a standardized mental picture that is held in common by members of a group and that represents an oversimplified opinion, prejudiced attitude, or uncritical judgement.”

Stereotypes are often one-dimensional, lacking depth and complexity and may be found offensive by readers. The worst stereotypes are created from a writer’s limited understanding of characters in a minority or disadvantaged group.

Such characters fall into stereotype when their primary purpose is to support the (often white, straight) protagonist, with no substantial character development themselves. Examples of potential stereotypes include: the gay best friend, the Asian tech-geek, the Arab terrorist etc.

It’s different if your story features, for example, a well-rounded, interesting Muslim character who is drawn towards fundamentalism for nuanced, sympathetic reasons. Then your characterisation should be full of depth and interest. See, for example, Fatima Bhutto’s The Runaways.

If, on the other hand, your protagonist is a white cop in New York foiling a terrorist plot, and your antagonist an Islamist bomber with only three lines of evil-sounding dialogue, your antagonist may well fall into an offensive stereotype.

Stock Characters

Stock character types (e.g. the Eccentric Investigator, the Mastermind Villain) are more typical than archetypes, yet more flexible than stereotypes.

You can think of stock characters as existing on a spectrum, with archetypes at one end, stereotypes at the other, and stock characters in the middle.

Because there exists a spectrum, there also exist grades of variation in terms of how stereotypical or how archetypal a particular stock character is.

Stock Character Meaning

Given the potential for offense if your stock character falls into the stereotype region of the spectrum, you may ask, why take the risk of using stock characters at all? Let’s explore the meaning and purpose of stock characters and how they add value to your story, when well-written.

The term stock character comes from the idea that certain character types can be imagined as stock on a supermarket shelf, from which a writer picks or chooses the type most useful to their story.

I imagine a fair few of you rolling your eyes at this description. Who’d want to do something so uninspired as pull characters off an imaginary supermarket shelf? A natural artistic reaction.

Nevertheless, when you examine successful stories (novels, movies, television shows, graphic novels, etc.) under a critical lens, you may realize how populated with stock characters these stories actually are.

The list of stock characters is so extensive, it can actually be hard to get away from them. Stock character types are so ubiquitous, it can be tricky to create a character that doesn’t somehow meet, explore or subvert a certain stock type.

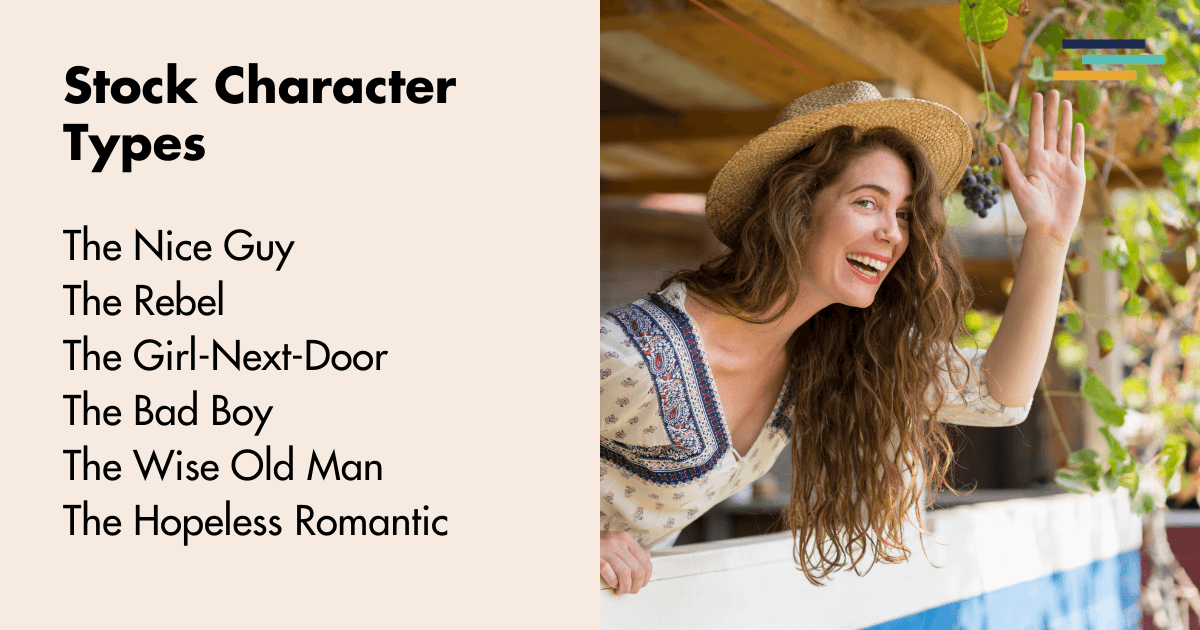

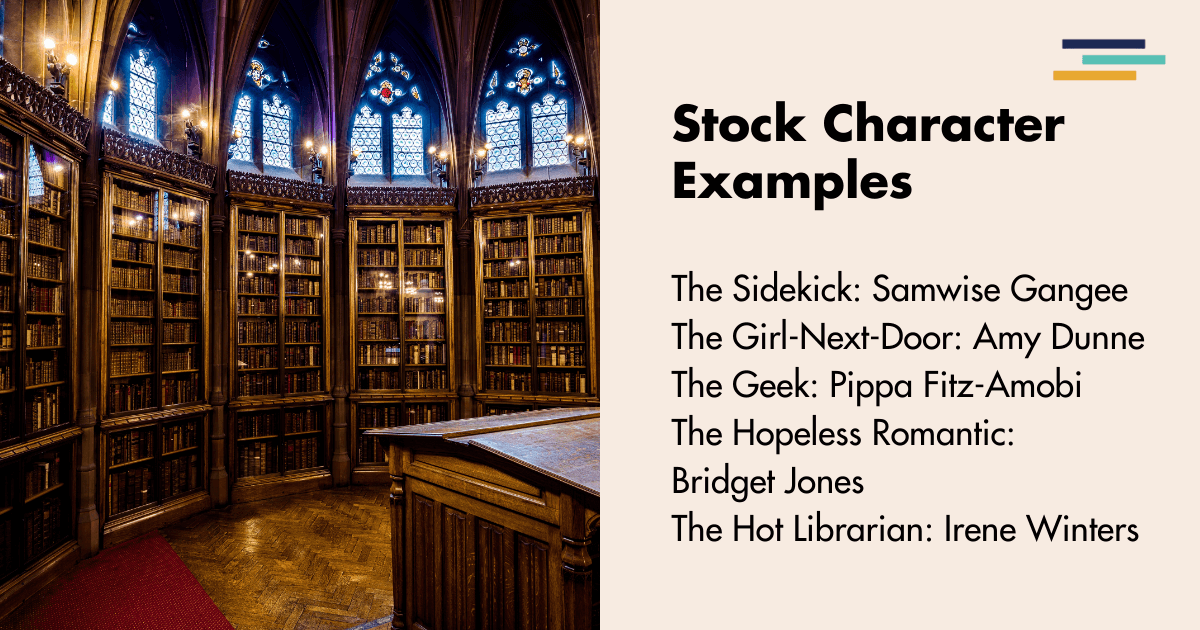

To demonstrate this conundrum, let’s look a sample selection of stock characters, including:

- The Nice Guy

- The Rebel

- The Girl-Next-Door

- The Bad Boy

- The Wise Old Man

- The Hopeless Romantic

That’s a pretty broad range of stock character types! Try writing a successful commercial romance that doesn’t somehow use one of the pre-existing stock characters, and you may find yourself struggling.

You may instead find it advantageous to lean in to the existence of stock characters, especially if you write genre fiction.

Why Use Stock Characters?

By understanding the different types, and gaining familiarity with how they’re portrayed in other stories, you can then make a conscious decision as to whether it will strengthen your story to use, explore, or subvert the specific stock character type you’re working with.

You’ll find certain genres particularly heavy in specific stock types: Young Adult High School stories, for example, are typically filled with Mean Girls, Nerds and Jocks. Crime stories abound with Hardboiled Detectives, Loveable Rogues, and Femme Fatales.

Genre readers love these stock characters as long as the stock character has depth and individuality. Most high schools do have a few popular pretty girls who bully others, and many police detectives do develop a degree of cynicism throughout their career, having been exposed to so much violence and hardship.

Potential Advantages and Pitfalls of Using Stock Characters

Advantage 1: The existence of certain types of stock characters also allows for side characters to be easily understood in their role, without the writer having to spend too much time developing them.

That’s why stock characters are particularly useful in screenplays, where time constraints may allow for side characters to have only a few lines. The viewer, in this case, knows exactly the type of character they’re dealing with straight away.

Along with these expectations, comes the possibility of subverting the type or expanding it as the story develops.

Advantage 2: Stock characters can provide instantly relatable, familiar conflict and tension, which can allow your story to pick up its pace and interest rapidly right from the start.

Potential Pitfall: Allowing your stock characters and their conflict to fall into stereotype, however, will make many readers roll their eyes and put down your book immediately.

Stock characters can be useful when a writer gives them enough complexity and depth to ensure they don’t fall into stereotype.

Stock Character Examples in Literature

The best way to show the value of stock characters is to look at well-written literary examples, examining whether they meet, explore, or subvert their type.

The Sidekick: Samwise Gangee from The Lord of the Rings, by J. R. Tolkein.

Sam’s purpose is to support Frodo and be optimistic when Frodo’s sad and strong when Frodo’s weak. Sam remains a constant reminder to Frodo of home, of what he’s fighting for. Sam’s loyalty towards Frodo shows us from the start that Frodo is a character worthy of respect and love.

Nevertheless, as the story develops, Sam becomes a realistic, believable character, existing independently of his friendship with Frodo. He grows jealous and judgemental when Frodo develops a friendship with Smeagol. At the story’s end, Sam turns to Rosie, not Frodo, for his happy ending.

Conclusion: Samwise Gangee meets the Sidekick stock character depiction. Nevertheless, Tolkein writes this character with sensitivity and depth.

The Girl-Next-Door: Amy Dunne in Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn

Amy’s the cool girl every man dreams of marrying.

When she goes missing, her diaries reveal her every thought is as typical Girl-Next-Door as any man could dream up. Pretty, but not overly-confident; intelligent, but not threateningly so. All she wants is a homely life with a Nice Guy. But, as the story develops, we start to question this stock character in myriad different ways…

Conclusion: With Amy Dunne, Gillian Flynn explores and subverts both the Girl-Next-Door and Femme Fatale stock character types.

The Wise Fool: The Fool in King Lear, by Willian Shakespeare

In this most tragic of tragedies, in a world turned upside-down, where Kings act like children and children act like Kings, the Fool, naturally, is the wisest of men. This Fool is so wise, we can never tell whether poetic wisdom pours from the mouths of babes, or whether the Fool knows his own intelligence.

Is he mad? Or is the world mad and he sane? Who can tell, in times of such social disorder?

Conclusion: With this Fool, Shakespeare meets and explores the stock character type to develop his key themes and imagery within the play.

The Geek: Pippa Fitz-Amobi in A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder, by Holly Jackson

Teenage Pip is highly intelligent and slightly obsessive. She’s focused on solving crime cases, not looking pretty.

But there’s nothing stereotypical about Pip, nor about how others see her. Her friends and social group, including her handsome love interest, all recognize her for the brilliant, strong-minded, determined, and loveable girl that she is.

Both this character and this book challenge stereotypical attitudes towards girls like Pip, commonly portrayed as Geeks, by showing her as a multi-dimensional, fascinating character, who uses her obsessive tendencies for the social good, gaining love and respect from the people around her.

Conclusion: Holly Jackson meets, explores and subtly subverts the Geek stock character type with her protagonist.

The Hopeless Romantic: Bridget Jones in Bridget Jones’s Diary, by Helen Fielding

Bridget’s obsessed with finding love. She feels like an outcast in society as a singleton. She’s not too bothered about her career, being willing to ditch her job after an affair with her boss turns sour.

Yet, while Bridget believes her entire value as a person turns around the success of her romantic relationships, we readers know otherwise.

We see Bridget as funny, kind, loyal to her friends, and ready to work for what she wants. We know Bridget’s value doesn’t hinge upon her romantic status. And it’s only when Bridget herself learns to understand her own worth, that she’ll have a chance at finding true love.

Conclusion: With Bridget, Fielding meets and explores the Hopeless Romantic stock character type.

The Hot Librarian: Irene Winters in The Invisible Library series, by Genevieve Cogman

Irene’s a Librarian. But not just any Librarian. She works for the Invisible Library, a multi-dimensional agency charged with holding in check the opposing forces of Order and Chaos, thus keeping the multiverse stable. Librarians like Irene achieve this through stealing original books from different universes, and storing them in the Invisible Library.

Q: But is Irene hot?

A: No idea. The story’s told primarily from Irene’s point-of-view, and she’s not that bothered about her looks. What she does care about is books.

Q: Do we care whether Irene is hot or not?

A: Not in the slightest. She’s far too cool for us to care about such superficial matters. There’s not a dragon, a faerie, or a book heist that our heroine can’t handle.

Q: Does anyone else in the story care whether Irene is hot or not?

A: Many of the male characters are attracted to her. But they’re attracted to her personality as well as her looks, her intelligence, abilities, general heroism, and sense of humor.

Conclusion: It’s definitely possible to fit Irene into the stock character type of Hot Librarian. But Cogman takes the stock character type and subtly subverts it, showing how this Librarian is worth much more than just her physical appearance.

List of Stock Characters

More stock characters exist than it would be possible to list here, so I’ll just take a few of the most popular ones:

- Action hero: Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins

- Airhead: Becky Bloomwood in Confessions of a Shopaholic, by Sophie Kinsella

- Crone: Bogdana in The Stolen Heir, by Holly Black

- Damsel in Distress: Guinevere in The Morte D’Arthur, by Thomas Mallory

- Femme Fatale: Rebecca in Rebecca, by Daphne duMaurier

- Loner: Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye, by J. D. Salinger

- Loveable Loser: Eyeore in Winne the Pooh, by A. A. Milne

- Mad Scientist: Dr Frankenstein in Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley

- Miser: Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens

- Outlaw: Edmond Dantes in The Count of Monte Christo, by Alexandre Dumas

- Starving Artist: Stephan Dedalus in Ulysses, by James Joyce

- Tomboy: Arya Stark in A Game of Thrones, by George R. R. Martin

- Yuppie: Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, by Bret Easton Ellis

How to Write Stock Characters: Tips

Beware of Stereotypes

Let’s start with the obvious. If your stock character has the potential for offensive stereotypes, understand this before writing your character. Consider how to avoid the pitfalls.

For example, if you want the Sidekick in your Crime novel to be a Sassy Latina junior detective, understand that this has been done before. Research why people may find this stereotype offensive or tiring. Then avoid these traps.

Don’t make your Sidekick exist purely as a convenient translator of Spanish to English for your (white, male) senior detective. Give her complexity and depth.

If you genuinely haven’t the available word count for such character development, then consider changing something important about the stereotype. For example, make her studious, shy and a native Portuguese-speaker, so your senior detective still has to rely on his high-school Spanish to get by with the Spanish-speaking gangs.

Meet, Explore, or Subvert Character Types

In certain genres, readers’ expectations must be met.

If writing romance, for example, your Hopeless Romantic protagonist must find love. You can explore what’s required for this to happen in more depth, as Fielding does in Bridget Jones’s Diary, but you’re limited in the ways you can subvert the Happily Ever After.

If your Hopeless Romantic ends up happily single, you’ve probably written a Coming-of-Age story rather than a traditional romance, and you need to market this as such.

If you’re writing literary fiction, readers will expect any stock character types to be explored and/or subverted, through detailed examination of their character.

For example, in Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, protagonist Theo Decker may seem like a Starving Artist type – but while this traditional stock character type sacrifices material wealth for the love of Art, Theo designs his skilful furniture forgeries purely for profit.

Give Stock Characters Individualistic Details

Even if your secondary stock character makes only a fleeting appearance, you want them to be realistic rather than plastic.

For example, beware describing your High School Mean Girl as just: A pretty, blonde cheerleader.

That’s a stereotype.

Consider adding unexpected details. Describe her instead, for example, as: Pretty, blonde and with a slight limp, which meant she could always find boys desperate to carry books around the school halls for her. Unable to try out for cheerleading squad due to her physical limitations, she instead ensured dressage became the activity all the cool girls wanted to do. And she sure knew how to make herself look good on a horse.

A few extra words, in these cases, can make for a far more interesting character.

Conclusion

By understanding how stock characters can enhance your story, as well as how to avoid the potential pitfalls of using them, you’ll be in a strong position to fill your novel with interesting characters who variously meet, explore, and subvert your readers’ expectations.