Oxford Languages defines a protagonist as:

- The leading character or one of the main characters in a play, film, novel etc.

- An advocate or champion of a particular cause or idea.

For a fictional character to be a protagonist, therefore, the story must revolve around them.

Moreover, for a fictional protagonist to resemble a real-life protagonist, one readers consider deserving of the title, this character must be prepared to champion the idea of the story.

A protagonist must embody the story’s key themes, drive the action forward, and overcome obstacles to achieve their goal.

Why Do Stories Need Protagonists?

Readers don’t identify with a story’s plot, setting or theme. Readers identify with its characters and their goals, motives and passions.

These characters don’t have to be human. They can be any animal (The Fantastic Mr Fox) or non-animal creature (R2-D2 in Star Wars), as long as they’re shown within the story as a sentient being that feels relatable thoughts and emotions.

Characters, through their decisions, feelings, and actions, are what drive a story’s plot. Without a protagonist, a story risks being overwhelmed by the various thoughts, goals, needs, and wants of the varying characters within the narrative.

Having a protagonist—a leading character with whom the reader can most identify with and care about—helps give coherence, meaning, and structure to the action within a story.

A story’s primary themes are usually related to the goals and motives of its protagonist (what they want), as well as what the protagonist lacks and their learning journey over the course of the narrative (what they need).

A proactive protagonist gives a story’s narrative a clear direction, which helps strengthen pacing. The questions which readers ask about the protagonist at the start of the story—will they achieve their goal? Will they grow and succeed in life? —are essential for keeping readers glued to the page.

Types of Protagonist

At Fictionary, we set out three types of protagonist:

- Single Protagonist: This is when a story has a single character with whom the reader should most identify. Harry Potter provides an example of a single protagonist.

- Dual Protagonists: This is when you have two main characters who share a single overarching story goal. Because of their shared goal, a success or failure for one is always a success or failure for the other. Thelma and Louise is a strong example of dual protagonists.

- Group Protagonist: In some stories, multiple characters carry equal claim to be called the protagonist. They form part of a group sharing a single story goal. Their success and failures, however, may not always rise and fall together; they may oppose each other along the way. For example, in Game of Thrones, all the humans form part of one group, with the ultimate story goal of defeating the White Walkers.

Examples of Protagonists

Protagonists in Harry Potter

We all know Harry as the boy who successfully drove the plot of seven stratospherically-successful novels.

But wait! You may ask. Did Harry actually drive the plot? Wasn’t Voldemort pulling all the strings?

An excellent question.

Harry falls into the hero archetype.

The hero often begins their story in a reactive manner, while the antagonist pushes forward their evil agenda. The hero’s learning journey centres around the switch from reactivity to proactivity, as they learn to fight for what they believe in. This shift from reactionary to true proactivity is traditionally found at the story’s midpoint.

In the first half of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Harry’s smaller scene goals are less heroic and more reactive: to read the mysterious letter from Hogwarts, to find a curse to use on his cousin Dudley, etc.

We need to see a protagonist chase goals from early in the story if we’re to root for them. But if they start their journey in an extremely heroic manner, there’ll be nothing for them to learn and no way to grow and change.

At the story’s fifty percent mark, Harry stands up to the classroom bully, Draco Malfoy, to defend his friend Neville Longbottom. In doing so, he risks his own safety and the prospect of expulsion (high stakes). This act of selfless bravery is arguably the moment Harry first becomes a hero, shifting from reactive to proactive in his fight to overcome evil. It’s an important step in his journey towards taking on the more powerful bully, Voldemort.

By building slowly up to this character-defining moment, readers can place themselves in Harry’s shoes more easily. It’s harder to identify with a protagonist who begins the story as a perfect hero.

A strong character growth arc makes Harry relatable and compelling. Harry’s internal motivation for his external goals is important. Motivation provides his character with depth, preventing him being two-dimensional and irritatingly good. We understand Harry’s motivations and internal goals from a strongly developed backstory; he’s an orphan who grew up being bullied.

In order to understand how Harry’s backstory influences him, we need access to his internal world. We need to see how he perceives what happens around him. This means we spend much of the story inside his point of view.

We see the emotional impact different scenes have on Harry and how this learning journey affects his overall character growth arc. Throughout the course of the narrative, Harry needs to learn to stand up to bullies and that people aren’t always who they appear to be on the surface. He learns that the worst bullies may pretend to be decent (Quirrel), whilst those who appear surliest, may be decent underneath (Snape). This is a critical lesson, teaching him to avoid snap judgements.

We understand the stakes if Harry fails to keep the philosopher’s stone form Voldemort and why these stakes are particularly important to Harry. It influences everyone in Harry’s world if Voldemort is reborn. But it influences Harry the most, since Voldemort is desperate to kill Harry.

Protagonists in Star Wars

Like Harry, Luke’s an archetypal hero protagonist. His core shift from reactive adventurer into proactive hero comes at the midpoint of Star Wars when he and Han Solo decide to rescue Princess Leia who is trapped aboard the Death Star.

Prior to the midpoint, Luke’s shorter scene goals are formed by him reacting to events as they happen. After the midpoint, he develops more purposeful scene goals, designed to take him closer towards his story goal—defeating the Death Star.

There’s high conflict, tension, movement, and stakes in all scenes. After Luke’s aunt and uncle are killed, the rebel fight becomes highly personal for him. Furthermore, as the trilogy develops, we’re shown how Luke’s backstory is intricately connected to the rebel cause.

The audio-visual aspects of the movie and the acting show us how each scene has a strong emotional impact on Luke, which keeps us emotionally engaged in his journey.

As Star Wars is a movie rather than a book, we’re not granted the same degree of insight into Luke’s internal thoughts as we are with Harry Potter. Nevertheless, we see the story primarily from his point of view, and we’re never in doubt that he’s the character whose story is being told.

Luke’s inner character arc is developed over the course of the entire trilogy. The first Star Wars film focuses primarily on his growth from naïve farm boy to rebel hero.

Over the course of the three movies, we see a more specific internal shift. Luke loses his only known family on the planet Tatooine early in the first film. But through learning to treat his father, Darth Vader, as a potential ally rather than an enemy, he eventually gains a real father who’s prepared to die for his son. This inner growth arc, looking at complex family relationships, is universal, relatable, and compelling.

Protagonists in Catcher in the Rye

Holden Caulfield’s an example of an anti-hero. These protagonists tend to lack the archetypal heroic motivations of helping others, instead being motivated primarily by self-interest.

Holden’s story goal is to seek meaning and truth in his life, unencumbered from the phoniness of the adult world he’s entering as a teenager.

His midpoint shift to proactivity happens when he hires a prostitute and decides he only wants to talk with her. At this point, he begins searching more proactively for authentic innocence and connection.

Holden’s an unreliable narrator seeking truth, a compellingly ironic juxtaposition for many readers.

We spend the entire novel deep inside Holden’s point-of-view narration and internal thoughts, keeping us closely connected to him.Yet even though we’re in his head, Holden is constantly in motion, driving the action.

We know from the story’s start that the stakes in play,Holden’s sanity, have already been lost. The tragic question which keeps readers hooked isn’t “will he overcome the odds?” but “what happened in New York to make him lose his mind?”

It’s a captivating story question, one that makes us care deeply about our doomed protagonist, even although he lacks many standard heroic qualities. His search for meaning in life is both endearing and relatable for many readers, both teenagers and adults. His inner character arc shows him moving from bitterness towards generosity, a growth arc that’s admirable.

The tragedy Salinger portrays in Catcher in the Rye is that learning important life lessons is insufficient to save Holden’s psychological health. He still concludes his story in a mental institution. In fact, it’s arguably the rejection of his broken, phony world which leads to Holden’s incarceration, making us question whether it’s him, or his world, which is insane.

How to Write a Compelling Protagonist

- Give your protagonist a compelling story goal, which they must proactively chase from the story’s midpoint onwards.

- Give your protagonist story-relevant scene goals throughout the entire story. This will help your protagonist remain sufficiently active in the first half of the story to help keep your readers rooting for them.

- Ensure that your protagonist faces real consequences if their goals fail. Stakes create tension, keeping readers invested in your protagonist’s journey.

- Protagonists grow through conflict. Your protagonist’s growth will only be compelling if your story’s conflict is likewise compelling. The antagonist, and the obstacles your protagonist faces along their journey, should form a substantial challenge to their scene goals and story goals.

- To give your protagonist depth, carefully develop their motivations, internal goals, and backstory.

- Ensure you spend sufficient narrative time in your protagonist’s point-of-view to show us how their history impacts their motivations, goals, and perceptions of their world.

- The protagonists of most commercial fiction stories undergo an internal growth arc (making them dynamic characters). Ensure you make this growth believable by showing how each success and failure, and the emotional impact this has on them, influences their change in attitude and beliefs. This will help you develop your story’s themes, as well as making your protagonist more relatable.

- If your protagonist fails, or refuses, to grow throughout the story (and is therefore a static character), ensure you’ve provided strong thematic reasons for this lack of change. Perhaps the protagonist’s tragic failure to change has led to the reader developing greater understanding of your story’s key themes (as in Shakespeare’s King Lear), or perhaps your protagonist has made a substantial change to their world, even if they haven’t changed themselves (as in the classic Western True Grit).

- Try to keep your protagonists active and in motion. It’s generally harder to root for a passive protagonist who sits still whilst the action takes place around them.

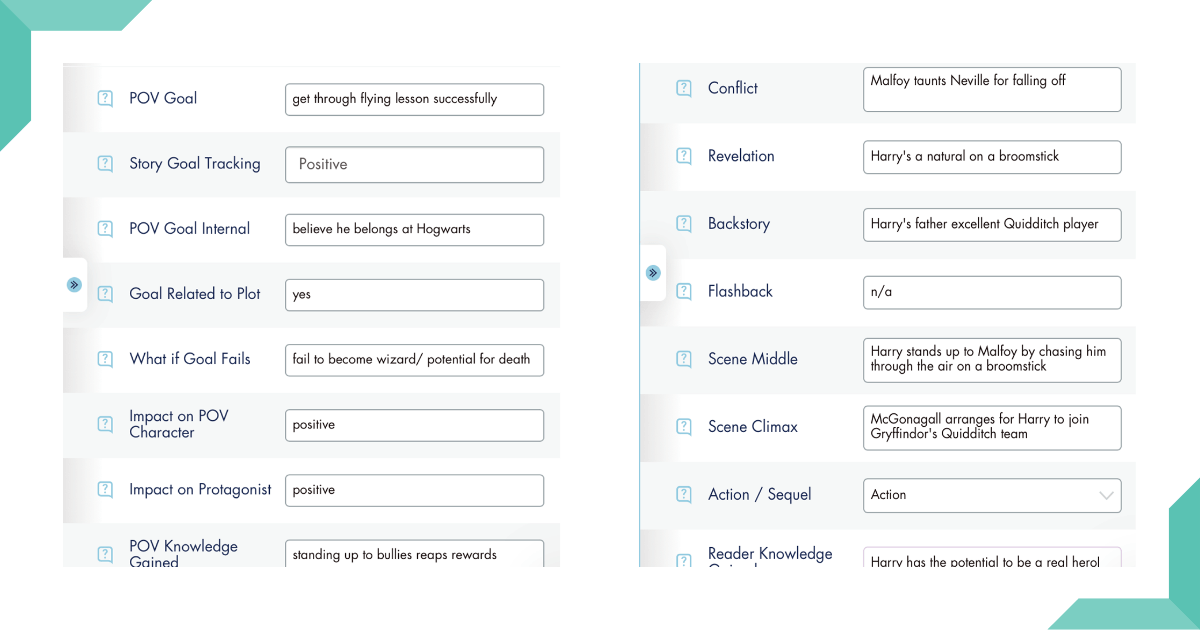

If this seems like a lot of information to keep a handle on, check out Fictionary Storyteller. Storyteller helps you check you’ve included all the necessary story elements in every scene. Here’s an example of the midpoint scene from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone: