Editing makes a story the best it can be by revising content, fixing errors, and ensuring the story engages readers. Every book needs editing, and revision is crucial to the writing process. If you’re considering becoming a developmental editor, get to know the various editing types and how they (and you) fit in the publishing process.

Writers experience anxiety when sharing their work and having it criticized. In addition, most reviewers are friends and colleagues, untrained in story design and giving effective feedback and supportive direction. Professional editors elevate manuscripts by applying specific skills and tools, including knowing how to express what matters.

There are different types and levels of editing. Developmental editing focuses on the big-picture aspects of a story. If you’re interested in becoming a developmental editor, it’s essential to understand how every type of editing serves the various stages of book creation.

What Are the Different Editing Types?

To understand the what or which of editing, consider the when. The path from idea to published book takes multiple steps: idea selection, multiple drafts to clarify the overall story and structure, revisions to polish the sentences, book design, printing, and distribution. The drafting and early revision stages focus on content, and the subsequent editing steps address language.

The broad editing categories—content and language—reflect revision timing, purpose, and focus. There is overlap, but don’t let that and the multiple names confuse you. Each has a particular role in shaping a well-crafted, polished manuscript ready for publication. The seven types of editing services are:

Content editing

- Book coaching

- Beta reading

- Manuscript evaluation

- Developmental editing

Language editing

- Line editing

- Copyediting

- Proofreading

Book Coaching: Book coaches help writers visualize, formulate and write their manuscript and agent pitches by delivering guidance, feedback, and accountability. Coaches must be familiar with story structure and plotting. Coaches review and give feedback on assignments and pages but do not write, correct, or revise (beyond some typos, etc.)

Beta Reading: Beta readers give reader-level feedback, which can highlight the parts of a story that work and don’t. Most beta reading is done by untrained friends, family, and writing colleagues. Editors also provide this service, offering skilled feedback. However, beta reads do not include editorial direction or revisions.

Manuscript Evaluation: A manuscript evaluation, or manuscript critique, discusses the story’s strengths and weaknesses and addresses character, plot, structure, dialogue, and pacing issues. A significant step up from a beta reading, these reports give feedback and suggest editorial next steps but do not revise or correct writing.

Developmental Editing: Developmental editing, also called story editing, substantive editing, structural editing, or content editing, is the most in-depth form of content editing. After the writer has revised to the best of their ability, a developmental editor analyzes, critiques, and makes suggestions to improve the story. A significant upgrade from a manuscript evaluation, developmental editing reports are comprehensive and include extensive inline comments, queries, and a book map or spreadsheet.

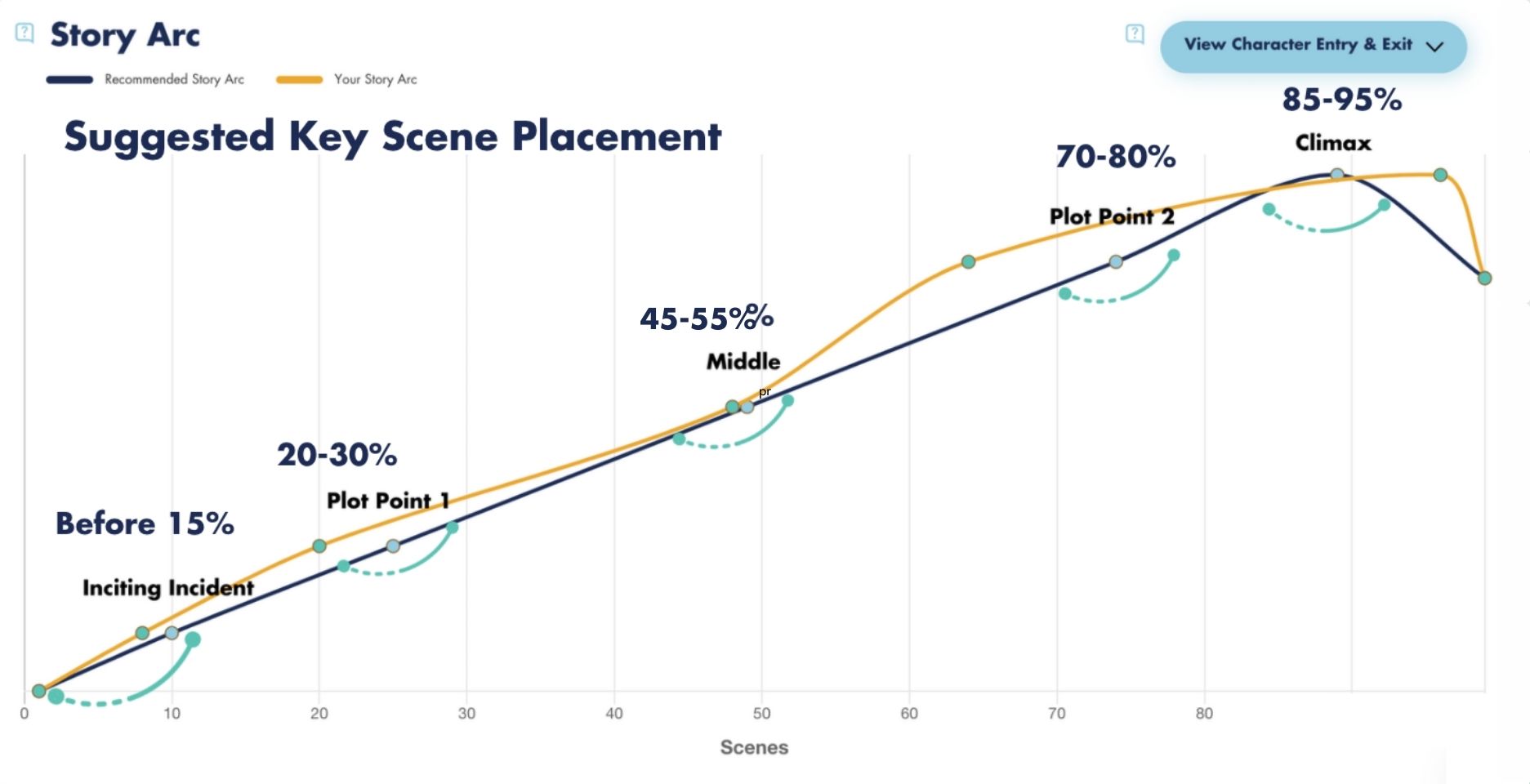

Showing a writer their story arc is key to the success of a development edit. Below is ab image of the story arc Fictionary StoryCoach draws automatically for you.

Line Editing: Line editing, also called heavy copyediting or stylistic editing, is performed after deciding on the overall story content. Line editing ensures each sentence is well-written, clear, and flows smoothly into the next. Line editors address awkward sentences, point of view errors, repetitive words, inconsistent verb tenses, and narrative logic. Line editors strive to maintain the author’s voice and the story’s tone and mood.

Copyediting: Copyeditors correct mechanical errors such as grammar, spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and numbering and ensure the style adheres to publishing standards. Most writers arrange this final polish before submitting to an agent or book designer.

Proofreading: Proofreading comes after the book design phase and corrects errors on formatted pages before printing and e-book setup. Proofreading does not conceptually change the overall or sentence-level story but ensures that book-ready pages are as error-free as possible.

What is Developmental Editing?

Of all editing types, developmental editing has the most significant impact on shaping the final story because it addresses the big-picture aspects. This type of editing focuses on the overall structure, theme, concept, and organization. The editor may suggest moving, deleting, or adding sections but typically doesn’t revise sentences.

The name “developmental” reflects the editor’s role—helping to develop the overall story. The term “story edit” reflects the expansive scope. Developmental editors ensure the manuscript has a clear purpose, meets genre conventions, and has a unified execution of all story elements. Developmental edits do not address language level issues because moving, deleting, and reshaping the story’s content will only undo any line and copyediting changes.

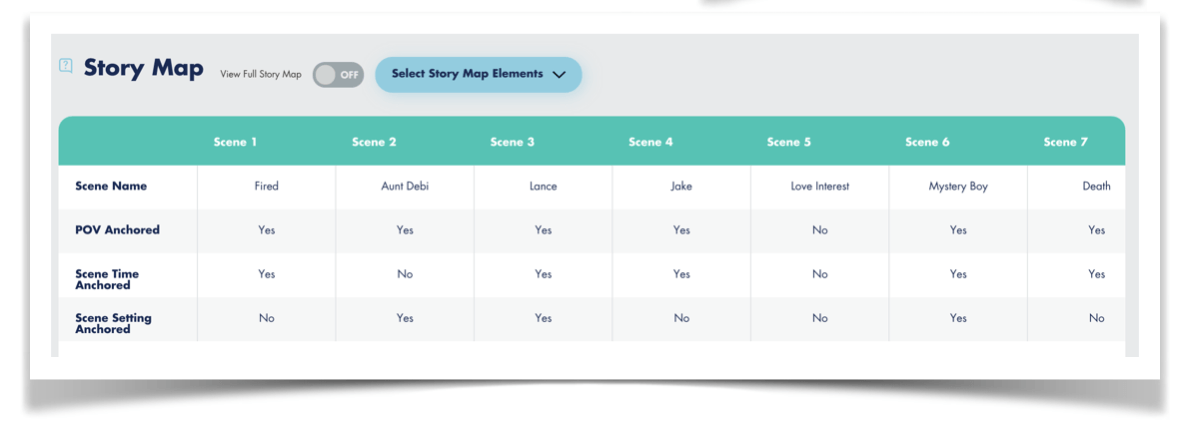

Developmental editing also requires that an editor evaluate story elements on a per scene basis as shown in the Fictionary Story Map below.

Developmental editing is equally essential for fiction (genre or literary) and nonfiction (memoir, creative nonfiction, academic, and how-to.) The goals for nonfiction include clear communication of the primary purpose, effective organization, and demonstration of the writer’s expertise, craft, and unique perspective; however, memoirs are handled like fiction.

What Does a Developmental Editor Do?

Specializing in developmental editing allows you to express your innate love of storytelling and propensity for analysis or organization. If you’re thinking about becoming a story editor, consider how you relate to and react to stories in all forms.

Do you find yourself flipping back to chapter three for the set-up of a later payoff? Are you the one who can explain in detail why a character’s action in the finale didn’t make sense given their earlier behavior? Can you see the plot twist coming a mile away? Can you skip over typographical errors without needing to correct them with a pen or mention it in a book review? Do you wonder what happened to character X from chapter two? If so, you have a knack for catching global story elements, and developmental editing may be a good fit.

A developmental editor requires good communication skills, keen reader-level skills, and familiarity with genre conventions. Story editors have sharp analytical skills, understand how story elements work with structure, and can formulate a revision implementation plan.

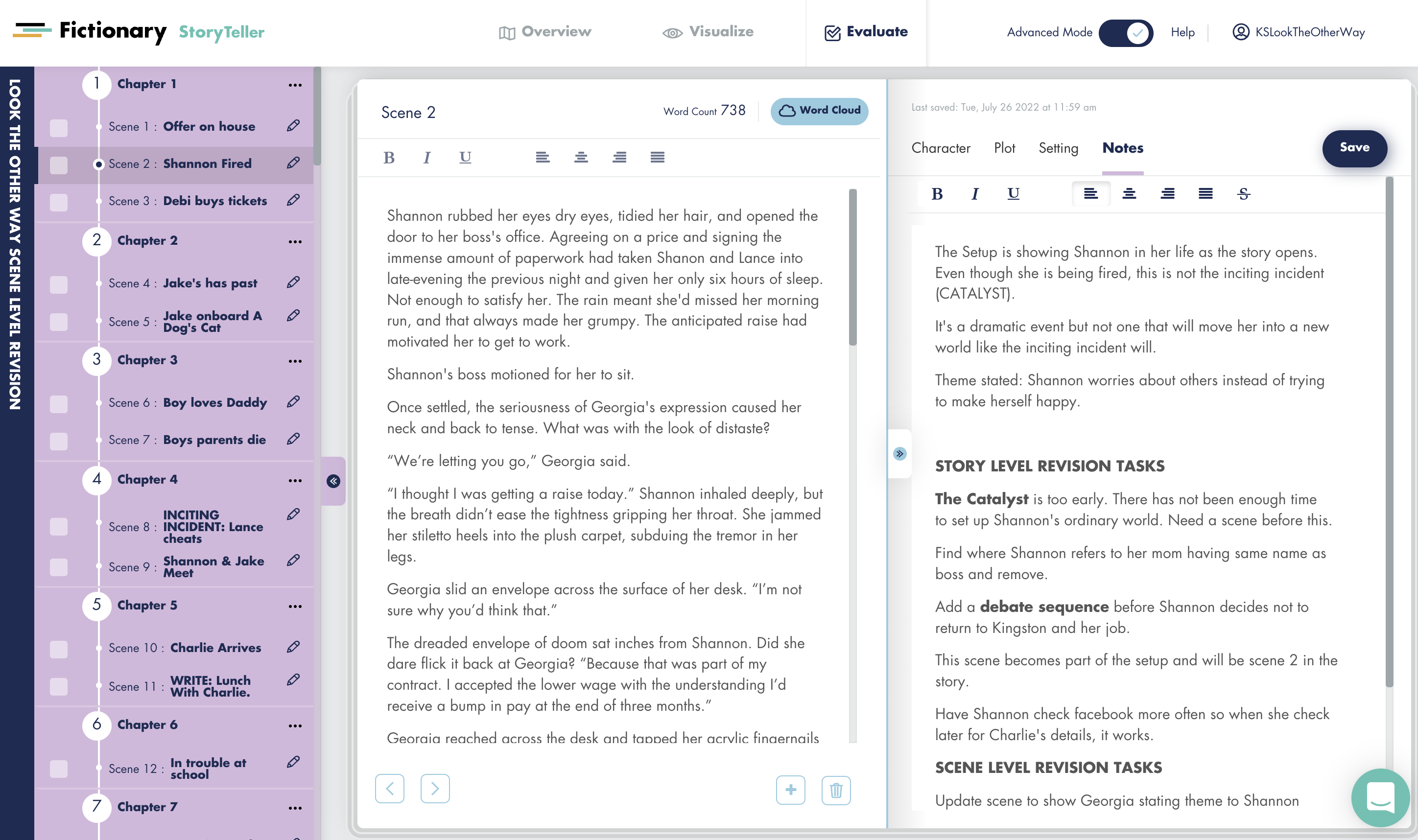

The Fictionary Notes per Scene feature is a great way to show the reader what each scene needs.

Writers may become developmental editors after revising their own stories or working with editors and becoming enamored with the process. Seeing how moving, deleting, or adding paragraphs, sentences, or scenes heightens a narrative is revelatory.

Copyeditors and proofreaders may become interested in developmental editing to explore their creative processes or to expand service offerings. Maybe they’ve recently noticed a talent for story structure analysis.

Perhaps you want to work with self-publishing authors or small publishing houses. They don’t have big budgets, and working with them may align with your business plan, mission, and values.

How to Become a Developmental Editor

To become a developmental editor, you will need training in writing craft and the tools and processes required to perform story edits. Tools include a word processor (Microsoft Word is the standard) and spreadsheet (such as Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets) for the story map.

How to Become an Editor Without a Degree

If you do not have a degree do not despair. There are many ways to become an editor without a traditional degree.

University extension writing programs (such as UCLA and the University of Chicago) offer developmental editing classes. Professional editing organizations (such as the Editorial Freelance Association in the US and the Chartered Institute of Editing and Proofreading in the UK) offer editing courses. Developmental editing training by professional editors can be found online at several sites, including Fictionary.co. Finally, publishing internships may provide learning opportunities, although not reliably. Whatever path you choose, always look for opportunities to connect and create community with other editors.

Fictionary offers a unique combination of story editing training and specialized software tools to aid analysis, visualization, and presentation, making a spreadsheet or detailed MS word knowledge unnecessary. If you choose to become a Fictionary Certified StoryCoach editor, you’ll train with cutting-edge tools and a dedicated and supportive group of professionals passionate about making books better.

Conclusion

Developmental editing is a rewarding specialty. The opportunity to help writers shape their work while tapping into your love of storytelling is satisfying.